By Joel Rubinoff The Record

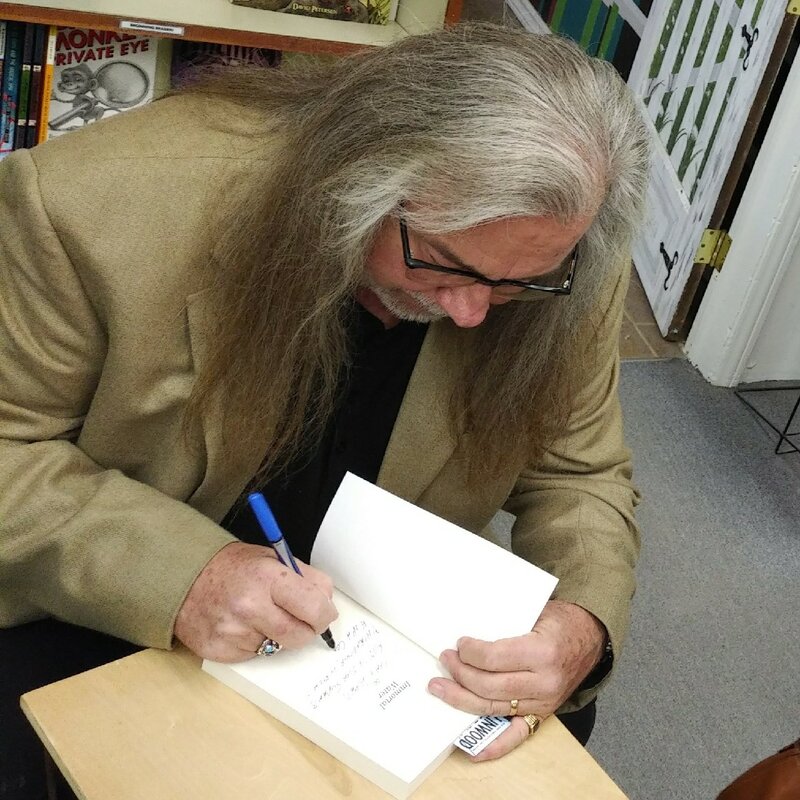

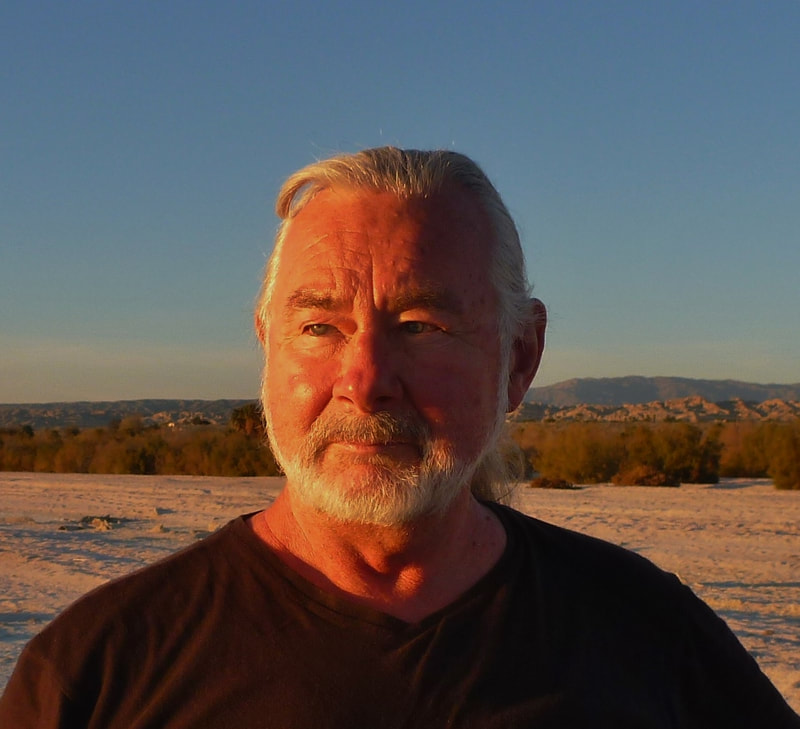

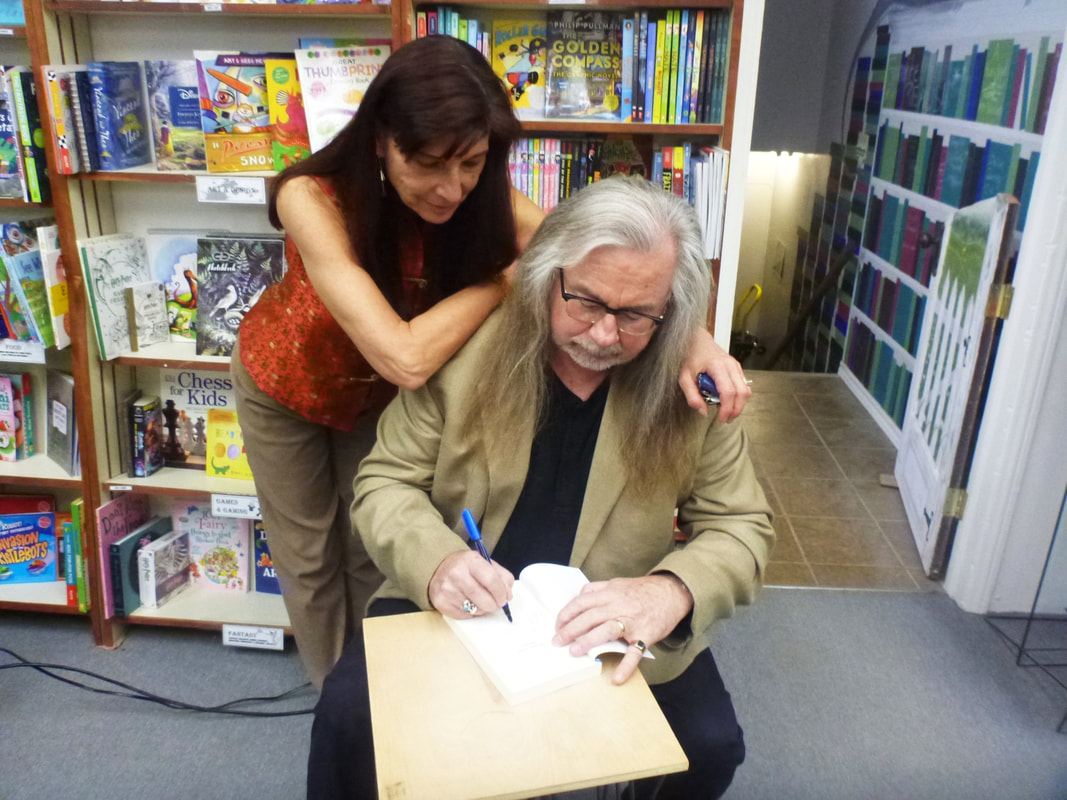

Even at 71, Brian Van Norman looks slightly radical, with his long white pony tail and Jerry Garcia whiskers, a laid back muckraker out to overthrow the status quo.

Not that it’s the most prominent thing about him.

Edging into seniorhood, the once rebellious student protester who made his mark as a high school teacher, theatre adjudicator, Stratford director and author of speculative novels about the ravages of technology is easygoing, solicitous, polite.

A free spirit with a pedigree.

“One of the reasons for my success is that I try to never repeat myself,” confides the personable shape-shifter. “I’m interested in people.”

I can vouch for that. Half way through our interview I notice he’s asking me all the questions as I recount the sordid details of my suburban childhood and how I got my first writing gig.

“And then, when I was seven ... hey, wait a minute!”

I’ll say one thing for Van Norman: he knows how to hang.

But if you look beyond the folksy author who speaks knowledgably about “qubits of subatomic size” and says he’s more of a “social pupa” than an actual butterfly, you see remnants of the 18-year-old who marched around the University of Waterloo arts quad in 1968 to protest the use of napalm in the Vietnam War.

“You can’t even call it sophisticated as political theatre,” laughs the genial nonconformist.

“In a brilliant piece of guerrilla protest, a Waterloo antiwar group announced it would demonstrate the horrors of napalm by burning a dog.

“The quad was crowded with people, some intending to rescue the dog, many just wanting to watch the confrontation, perhaps a few concentrating on the actual issue — the savage weapons being deployed in Southeast Asia. On schedule, out came the protesters, bringing their dog to the fire and perhaps you can guess what kind of dog it was.”

Judging by your tone, a hotdog?

“Schneider’s finest.”

They were crazy times for the burgeoning student activist, who occupied the university’s administration office in a protest four years later, sang in a rock band and lived in Toronto’s hippie Yorkville district, where he saw Joni Mitchell perform in coffee houses, and moved back to Waterloo when the stench of drugs became impossible to ignore.

“I’m easily addicted and knew I wouldn’t make it,” confides the Orangeville native, who moved to Waterloo to attend university.

“But as a kid from a small town I revelled in the freedoms of the village and the exchange of ideas among people of different ideologies and backgrounds. I evolved into adulthood amid the characters of that place and time.”

Strategically positioned at the front end of the baby boom in the days when a general arts degree was a ticket to job security, he rode the wave of societal change straight into a generational clash with his conservative war vet dad.

“He was a very good father who was a kind and generous man,” he notes with the perspective of half a century.

“His service in World War II and the culture of his development a generation earlier made him a man who found it difficult to deal with a son in the midst of a cultural revolution. We clashed often.”

It was the tenor of the times. Old vs. Young. Don’t trust anyone over 30. Turn on, tune in, drop out.

“I came of age in one of the most powerfully dynamic times since the Renaissance,” insists Van Norman. “A free spirit is not the easiest kind of person to live with.”

It’s worth noting that despite his anti-establishment perspective, he didn’t drop out and move up north to live on a commune.

He didn’t blow out his brains on mind-expanding drugs in search of higher consciousness.

He didn’t throw caution to the wind, tilt at windmills and devote his life to fighting the establishment.

At 23, he snagged a job as a drama teacher at Cambridge’s Glenview Park Secondary School and, later, at Kitchener’s Forest Heights Collegiate.

“I think in most life matters, though I’m impulsive, I’m also practical,” he offers succinctly.

“I did not reject society. I tried to take a place within it and change what I could. That practicality was given to me by my parents. It also resulted in heated debates with my friends. One couple still believe I sold out to the establishment and I haven’t spoken with them for 40 years.”

People are complicated. Values shift.

In the end, Van Norman — artistic temperament and all — was drawn to hard work and reaching not just inward, but out.

“My whole career was an accident!” he confides in his wry, soft-spoken way.

“I was an English major with a half credit in theatre. Three weeks into the school year, both theatre teachers resigned. The principal called me into his office and said ‘I see you have a theatre background.’

“I said ‘I have half a credit. I got it to meet girls.’

“He said ‘Well, you’re gonna be meeting a lot of them now!’”

That half credit would be the key to his future as a department head, award-winning playwright, adjudicator at the former Sears Drama Festival and full-fledged theatre director.

After retirement, he travelled the world and embarked on a second career as a historical fiction novelist.

Which brings us to today, on a concrete bench in the rusted shadows of a repurposed Kitchener tire plant, where the COVID lockdown gives this revamped tech hub an eerie stillness as two worlds collide in one amalgamated glop of concrete.

It’s a perfect backdrop for Van Norman’s trilogy, a past, present and future look at the ravages of tech, with its soon-to-be-released middle instalment set in transformative Waterloo Region.

“It explores humanity’s interactions and relations with machines,” he explains of its thematic thrust.

“I try to infuse my characters with a sense of complexity beyond — or beneath — their more obvious character traits.”

“Against the Machine: Luddites” — dubbed “Quentin Tarantino meets Jane Austen” -- is set during the Industrial Revolution of 1812 England, where mill masters replace men with machines and Luddite rebels smash them to pieces.

“Against the Machine: Manifesto” (available Oct. 1) — dubbed “Breaking Bad Comes To Waterloo” — is set in 2012 Waterloo and tells the story of a dependable family man who loses his manufacturing job through corporate downsizing and, with no sense of purpose, hatches a plot for revenge.

“Against the Machine: Involution” (in progress) — dubbed “Carbon Vs. Silicon: Evolution turned upside down” -- is set in 2212 on “a broken planet” where two races face off against each other and the planet itself.

The unifying theme, as befits a novel by a former hippie who grew up reading “Brave New World,” “War and Peace” and — this would explain the exciting plot twists — “The Hardy Boys,” is the unyielding resolve of the human spirit.

“I’m concerned about where tech is leading us,” sums up the pensive author. “Because at some point we’ll hit the ‘Moment of Singularity’ where a machine is going to discover an error in its programming and make a fix before its operator. At that moment, it doesn’t need us anymore.

“Once we have a superintelligent A.I., it’ll be able to create a better version of itself. This kind of a race would lead to an intelligence explosion and leave old poor us — simple biological machines that we are — far behind.”

That sounds nuts, I tell him. Computers can’t think on their own.

“I remember reading Dick Tracy comics when I was 10 and thinking ‘Wouldn’t it be neat to have a watch that would talk to me!’” he responds, pointing at his knock-off Apple wristband, a minicomputer with Siri integration that, yes, talks to him.

“All I’m saying is that in my lifetime, when I was six, I remember hitching a ride on the back of a milk wagon pulled by a horse through Guelph. Now I can talk to all of my friends around the world literally by turning on my computer.”

I can see why this idea fascinates him — the social disruptions from tech rival the protest culture that defined his youth.

It is, in fact, what links the 18-year-old idealist pushing for change with the seasoned 71-year-old who travels the world in search of “holes in history” to fill with fanciful notions of what might have been and what could be in the years ahead: a ragged sense of optimism, punked by human experience.

“I tend to present myself as a cynic, hiding the vulnerable idealist inside,” he notes when pressed.

“I don’t think I could write (my books) if I thought the world would blow up.”

As we say goodbye, I have one final question: “That hotdog protest that caused such an uproar — did it do any good?”

Van Norman laughs, voice thick with optimism: “Well,” he points out, “the Vietnam War is over!”

For more info, go to www.authorbrianvannorman.com.

Even at 71, Brian Van Norman looks slightly radical, with his long white pony tail and Jerry Garcia whiskers, a laid back muckraker out to overthrow the status quo.

Not that it’s the most prominent thing about him.

Edging into seniorhood, the once rebellious student protester who made his mark as a high school teacher, theatre adjudicator, Stratford director and author of speculative novels about the ravages of technology is easygoing, solicitous, polite.

A free spirit with a pedigree.

“One of the reasons for my success is that I try to never repeat myself,” confides the personable shape-shifter. “I’m interested in people.”

I can vouch for that. Half way through our interview I notice he’s asking me all the questions as I recount the sordid details of my suburban childhood and how I got my first writing gig.

“And then, when I was seven ... hey, wait a minute!”

I’ll say one thing for Van Norman: he knows how to hang.

But if you look beyond the folksy author who speaks knowledgably about “qubits of subatomic size” and says he’s more of a “social pupa” than an actual butterfly, you see remnants of the 18-year-old who marched around the University of Waterloo arts quad in 1968 to protest the use of napalm in the Vietnam War.

“You can’t even call it sophisticated as political theatre,” laughs the genial nonconformist.

“In a brilliant piece of guerrilla protest, a Waterloo antiwar group announced it would demonstrate the horrors of napalm by burning a dog.

“The quad was crowded with people, some intending to rescue the dog, many just wanting to watch the confrontation, perhaps a few concentrating on the actual issue — the savage weapons being deployed in Southeast Asia. On schedule, out came the protesters, bringing their dog to the fire and perhaps you can guess what kind of dog it was.”

Judging by your tone, a hotdog?

“Schneider’s finest.”

They were crazy times for the burgeoning student activist, who occupied the university’s administration office in a protest four years later, sang in a rock band and lived in Toronto’s hippie Yorkville district, where he saw Joni Mitchell perform in coffee houses, and moved back to Waterloo when the stench of drugs became impossible to ignore.

“I’m easily addicted and knew I wouldn’t make it,” confides the Orangeville native, who moved to Waterloo to attend university.

“But as a kid from a small town I revelled in the freedoms of the village and the exchange of ideas among people of different ideologies and backgrounds. I evolved into adulthood amid the characters of that place and time.”

Strategically positioned at the front end of the baby boom in the days when a general arts degree was a ticket to job security, he rode the wave of societal change straight into a generational clash with his conservative war vet dad.

“He was a very good father who was a kind and generous man,” he notes with the perspective of half a century.

“His service in World War II and the culture of his development a generation earlier made him a man who found it difficult to deal with a son in the midst of a cultural revolution. We clashed often.”

It was the tenor of the times. Old vs. Young. Don’t trust anyone over 30. Turn on, tune in, drop out.

“I came of age in one of the most powerfully dynamic times since the Renaissance,” insists Van Norman. “A free spirit is not the easiest kind of person to live with.”

It’s worth noting that despite his anti-establishment perspective, he didn’t drop out and move up north to live on a commune.

He didn’t blow out his brains on mind-expanding drugs in search of higher consciousness.

He didn’t throw caution to the wind, tilt at windmills and devote his life to fighting the establishment.

At 23, he snagged a job as a drama teacher at Cambridge’s Glenview Park Secondary School and, later, at Kitchener’s Forest Heights Collegiate.

“I think in most life matters, though I’m impulsive, I’m also practical,” he offers succinctly.

“I did not reject society. I tried to take a place within it and change what I could. That practicality was given to me by my parents. It also resulted in heated debates with my friends. One couple still believe I sold out to the establishment and I haven’t spoken with them for 40 years.”

People are complicated. Values shift.

In the end, Van Norman — artistic temperament and all — was drawn to hard work and reaching not just inward, but out.

“My whole career was an accident!” he confides in his wry, soft-spoken way.

“I was an English major with a half credit in theatre. Three weeks into the school year, both theatre teachers resigned. The principal called me into his office and said ‘I see you have a theatre background.’

“I said ‘I have half a credit. I got it to meet girls.’

“He said ‘Well, you’re gonna be meeting a lot of them now!’”

That half credit would be the key to his future as a department head, award-winning playwright, adjudicator at the former Sears Drama Festival and full-fledged theatre director.

After retirement, he travelled the world and embarked on a second career as a historical fiction novelist.

Which brings us to today, on a concrete bench in the rusted shadows of a repurposed Kitchener tire plant, where the COVID lockdown gives this revamped tech hub an eerie stillness as two worlds collide in one amalgamated glop of concrete.

It’s a perfect backdrop for Van Norman’s trilogy, a past, present and future look at the ravages of tech, with its soon-to-be-released middle instalment set in transformative Waterloo Region.

“It explores humanity’s interactions and relations with machines,” he explains of its thematic thrust.

“I try to infuse my characters with a sense of complexity beyond — or beneath — their more obvious character traits.”

“Against the Machine: Luddites” — dubbed “Quentin Tarantino meets Jane Austen” -- is set during the Industrial Revolution of 1812 England, where mill masters replace men with machines and Luddite rebels smash them to pieces.

“Against the Machine: Manifesto” (available Oct. 1) — dubbed “Breaking Bad Comes To Waterloo” — is set in 2012 Waterloo and tells the story of a dependable family man who loses his manufacturing job through corporate downsizing and, with no sense of purpose, hatches a plot for revenge.

“Against the Machine: Involution” (in progress) — dubbed “Carbon Vs. Silicon: Evolution turned upside down” -- is set in 2212 on “a broken planet” where two races face off against each other and the planet itself.

The unifying theme, as befits a novel by a former hippie who grew up reading “Brave New World,” “War and Peace” and — this would explain the exciting plot twists — “The Hardy Boys,” is the unyielding resolve of the human spirit.

“I’m concerned about where tech is leading us,” sums up the pensive author. “Because at some point we’ll hit the ‘Moment of Singularity’ where a machine is going to discover an error in its programming and make a fix before its operator. At that moment, it doesn’t need us anymore.

“Once we have a superintelligent A.I., it’ll be able to create a better version of itself. This kind of a race would lead to an intelligence explosion and leave old poor us — simple biological machines that we are — far behind.”

That sounds nuts, I tell him. Computers can’t think on their own.

“I remember reading Dick Tracy comics when I was 10 and thinking ‘Wouldn’t it be neat to have a watch that would talk to me!’” he responds, pointing at his knock-off Apple wristband, a minicomputer with Siri integration that, yes, talks to him.

“All I’m saying is that in my lifetime, when I was six, I remember hitching a ride on the back of a milk wagon pulled by a horse through Guelph. Now I can talk to all of my friends around the world literally by turning on my computer.”

I can see why this idea fascinates him — the social disruptions from tech rival the protest culture that defined his youth.

It is, in fact, what links the 18-year-old idealist pushing for change with the seasoned 71-year-old who travels the world in search of “holes in history” to fill with fanciful notions of what might have been and what could be in the years ahead: a ragged sense of optimism, punked by human experience.

“I tend to present myself as a cynic, hiding the vulnerable idealist inside,” he notes when pressed.

“I don’t think I could write (my books) if I thought the world would blow up.”

As we say goodbye, I have one final question: “That hotdog protest that caused such an uproar — did it do any good?”

Van Norman laughs, voice thick with optimism: “Well,” he points out, “the Vietnam War is over!”

For more info, go to www.authorbrianvannorman.com.

It's a Long Story: Brian Van Norman on His New Novel and Class Struggle's Past and Present

While the characters of author Brian Van Norman's new historical fiction novel Against the Machine: Luddites (Guernica Editions) exist within the hardscrabble manufacturing towns of 19th century Britain, their struggle is easily relatable to those suffering the effects of an increasingly tech-focused economy in our present day.

As their nation wages a bloody war against Napoleon's army, English factory-owners begin to welcome new technology, replacing human labour with automation and the promise of a richer bottom-line. Faced with the loss of livelihood, one young man leads a violent resistance against the rising tide. As the entire country trembles in the grip of violence and uncertainty, the British government relocates more troops to Northern England, trying to quell the outbreak of homegrown terrorism.

Against the Machine: Luddites follows a diverse group of individuals during this chaotic chapter of human history, tracing their relationships and experiences against a backdrop of desperate acts and immense political corruption.

We're very excited to have Brian at Open Book today to discuss the many changes his manuscript endured since its inception, meeting a new friend during a research trip to England, and the disturbing similarities between the Luddites' struggle and our current economic imbalance.

Open Book:Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Brian Van Norman:The first time I considered this concept was during the financial crisis of 2008, when thousands were thrown out of manufacturing jobs while an elite technologist class maintained high salaries. I watched the beginning of economic inequity, realizing that our 21st century society was only slightly better than the 19th century at resolving this boom/bust economy as new technologies altered the workplace.

In 1812, there was no welfare. In 2012, there were low-paid service jobs. There have been attempts at upgrading education, with slogans like “life long learning” describing the desperation and mass migrations by the poor to find any jobs to keep them solvent.

I believe it is common knowledge now that half of the world’s net wealth belongs to the top 1% while the bottom 90% holds only 15%. According to a 2017 Oxfam report, the top eight richest billionaires own as much combined wealth as “half the human race”.

I first wrote the prologue for Against the Machine: Luddites to get a sense of the style I would need to write the novel itself. I began by writing in a west Yorkshire dialect but, recognizing its complexity, eventually found a happy middle with just enough dialect wordage to give the novel a sense of time and place.

OB:How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

BVN:Against the Machine: Luddites is a novel about the Luddites of 1812 Northern England who, when thrown out of work by new technology, attempted to stop the future by destroying the machines which replaced them. So threatened was the British government that more troops were sent to Northern England than were fighting Napoleon in that year.

That period so reflects our own with mass migrations, trade deals in tatters, economic tribalism between haves and have-nots, and acts of terrorism brought on by desperation.

Through my initial research I discovered much of North England to have been affected by the Luddite movement. After having stayed there a while, I decided on Yorkshire, with its brooding moors and old ruins of woollen manufactories. Also, a particular event occurred there which enabled me to stipulate the positions of every side of the rising.

OB:Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

BVN:The entire novel constantly changed through its drafts as I found more depth in the characters I had chosen. Sometimes I followed my start plan, but in many other situations those characters demanded their own pathways.

The most significant change was because of George Mellor’s time in prison. He had discovered a philosophy to explain his complex relations since joining the Luddite cause. Though rather mystical, it gave the story a spiritual sense it had been missing up to that point. Of course his death, historically, was to be the climax of the novel. I discovered, however, as he had, that others live on. I found myself focusing on those most damaged by the passage of that year; those who lived amidst the terror yet were finding their ways to survive it. It led to an epilogue and now a sequel, set in 2012.

OB:Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

BVN:Perhaps my most preferred character in the novel is the most complex. Mary Buckworth, a parson’s wife with a mind much more abundant than his, takes a lover in the most forbidden societal gesture a woman of that time could make. She attempts to find her way through a middle ground of love and duty, but it inevitably collapses on her. Her words: “I have nothing left, George. Oh, I own this baggage around me but I’ve nothing left. I am the Luddite of my own life.”

OB:If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

BVN:If we don’t manage these machines and ourselves who make them, if we don’t marry what we make with who we are … then we’ll all become nowt but slaves!

This statement, I believe, is the crux of social and technological evolution on earth. In research for the sequel, “Against the Machine: Manifesto”, I have found this statement at the heart of most neo-Luddite materials I have researched.

This is not going away. We humans will always quest for what we believe is better, even when it may not be.

OB:Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

BVN:Research is at the heart of most historical novels and this one was no different. There were plenty of diaries, military reports, historical analyses and other sources to look to while creating as realistic a world as possible with the stimulation of fiction to power it. There is a substantial reference list at the end of the novel.

Yet there are even more effective methods of research, the most important of which is visiting the ground where these events occurred. In some places it can be a wild land, the great moors of the Peak District Dales and the West Riding of Yorkshire. In others, one can glimpse the ruins of old mills and manufactories through greenery as nature returns to take back its own.

And, of course, there are the great cities of the north: Manchester, Liverpool, Huddersfield, Leeds, and York with their fine museums to assist a researcher.

As well, there are the memories and legends. In some of the towns, there are people living in the homes of their two hundred-year-old ancestors. Their stories can be as enlightening as any historical tome.

OB:What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

BVN:More gratifying than strange, I wrote to the Huddersfield Historical Society, telling them what I was planning and asking if they could help. Within a week, I was sent the name of a gentleman who was not only an archeologist but an anarchist and specialist in Luddism in the West Country of York. I was to stay at his two hundred-year-old cottage, and we would be driven by his wife to places I’d researched and others I’d never heard of until meeting this erudite guide and teacher.

I met him on a hot summer day outside his cottage. He was working on a paper and drinking Guinness. I joined him and we simply talked until dark, not always about my research. By the time that evening ended and the next day of touring began, he and I had become friends, as though our meeting was meant to have happened. Everything he explained to me was balanced, and every question I asked him was answered with clarity and aplomb.

We are still friends. I hope to return to Yorkshire to launch the novel this spring.

While the characters of author Brian Van Norman's new historical fiction novel Against the Machine: Luddites (Guernica Editions) exist within the hardscrabble manufacturing towns of 19th century Britain, their struggle is easily relatable to those suffering the effects of an increasingly tech-focused economy in our present day.

As their nation wages a bloody war against Napoleon's army, English factory-owners begin to welcome new technology, replacing human labour with automation and the promise of a richer bottom-line. Faced with the loss of livelihood, one young man leads a violent resistance against the rising tide. As the entire country trembles in the grip of violence and uncertainty, the British government relocates more troops to Northern England, trying to quell the outbreak of homegrown terrorism.

Against the Machine: Luddites follows a diverse group of individuals during this chaotic chapter of human history, tracing their relationships and experiences against a backdrop of desperate acts and immense political corruption.

We're very excited to have Brian at Open Book today to discuss the many changes his manuscript endured since its inception, meeting a new friend during a research trip to England, and the disturbing similarities between the Luddites' struggle and our current economic imbalance.

Open Book:Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Brian Van Norman:The first time I considered this concept was during the financial crisis of 2008, when thousands were thrown out of manufacturing jobs while an elite technologist class maintained high salaries. I watched the beginning of economic inequity, realizing that our 21st century society was only slightly better than the 19th century at resolving this boom/bust economy as new technologies altered the workplace.

In 1812, there was no welfare. In 2012, there were low-paid service jobs. There have been attempts at upgrading education, with slogans like “life long learning” describing the desperation and mass migrations by the poor to find any jobs to keep them solvent.

I believe it is common knowledge now that half of the world’s net wealth belongs to the top 1% while the bottom 90% holds only 15%. According to a 2017 Oxfam report, the top eight richest billionaires own as much combined wealth as “half the human race”.

I first wrote the prologue for Against the Machine: Luddites to get a sense of the style I would need to write the novel itself. I began by writing in a west Yorkshire dialect but, recognizing its complexity, eventually found a happy middle with just enough dialect wordage to give the novel a sense of time and place.

OB:How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

BVN:Against the Machine: Luddites is a novel about the Luddites of 1812 Northern England who, when thrown out of work by new technology, attempted to stop the future by destroying the machines which replaced them. So threatened was the British government that more troops were sent to Northern England than were fighting Napoleon in that year.

That period so reflects our own with mass migrations, trade deals in tatters, economic tribalism between haves and have-nots, and acts of terrorism brought on by desperation.

Through my initial research I discovered much of North England to have been affected by the Luddite movement. After having stayed there a while, I decided on Yorkshire, with its brooding moors and old ruins of woollen manufactories. Also, a particular event occurred there which enabled me to stipulate the positions of every side of the rising.

OB:Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

BVN:The entire novel constantly changed through its drafts as I found more depth in the characters I had chosen. Sometimes I followed my start plan, but in many other situations those characters demanded their own pathways.

The most significant change was because of George Mellor’s time in prison. He had discovered a philosophy to explain his complex relations since joining the Luddite cause. Though rather mystical, it gave the story a spiritual sense it had been missing up to that point. Of course his death, historically, was to be the climax of the novel. I discovered, however, as he had, that others live on. I found myself focusing on those most damaged by the passage of that year; those who lived amidst the terror yet were finding their ways to survive it. It led to an epilogue and now a sequel, set in 2012.

OB:Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

BVN:Perhaps my most preferred character in the novel is the most complex. Mary Buckworth, a parson’s wife with a mind much more abundant than his, takes a lover in the most forbidden societal gesture a woman of that time could make. She attempts to find her way through a middle ground of love and duty, but it inevitably collapses on her. Her words: “I have nothing left, George. Oh, I own this baggage around me but I’ve nothing left. I am the Luddite of my own life.”

OB:If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

BVN:If we don’t manage these machines and ourselves who make them, if we don’t marry what we make with who we are … then we’ll all become nowt but slaves!

This statement, I believe, is the crux of social and technological evolution on earth. In research for the sequel, “Against the Machine: Manifesto”, I have found this statement at the heart of most neo-Luddite materials I have researched.

This is not going away. We humans will always quest for what we believe is better, even when it may not be.

OB:Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

BVN:Research is at the heart of most historical novels and this one was no different. There were plenty of diaries, military reports, historical analyses and other sources to look to while creating as realistic a world as possible with the stimulation of fiction to power it. There is a substantial reference list at the end of the novel.

Yet there are even more effective methods of research, the most important of which is visiting the ground where these events occurred. In some places it can be a wild land, the great moors of the Peak District Dales and the West Riding of Yorkshire. In others, one can glimpse the ruins of old mills and manufactories through greenery as nature returns to take back its own.

And, of course, there are the great cities of the north: Manchester, Liverpool, Huddersfield, Leeds, and York with their fine museums to assist a researcher.

As well, there are the memories and legends. In some of the towns, there are people living in the homes of their two hundred-year-old ancestors. Their stories can be as enlightening as any historical tome.

OB:What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

BVN:More gratifying than strange, I wrote to the Huddersfield Historical Society, telling them what I was planning and asking if they could help. Within a week, I was sent the name of a gentleman who was not only an archeologist but an anarchist and specialist in Luddism in the West Country of York. I was to stay at his two hundred-year-old cottage, and we would be driven by his wife to places I’d researched and others I’d never heard of until meeting this erudite guide and teacher.

I met him on a hot summer day outside his cottage. He was working on a paper and drinking Guinness. I joined him and we simply talked until dark, not always about my research. By the time that evening ended and the next day of touring began, he and I had become friends, as though our meeting was meant to have happened. Everything he explained to me was balanced, and every question I asked him was answered with clarity and aplomb.

We are still friends. I hope to return to Yorkshire to launch the novel this spring.

Author Brian Van Norman in The Reading Room

The room is softly lit, the walls lined with deep rich mahogany shelves filled with books and as you enter you notice there are still a few empty seats. A low murmur of amiable voices gently greets your ears and immediately you sense you are among friends. You sink down into the arms of a luxuriously padded wing back chair savoring the feel and scent of its buttery soft leather as all your cares drift away.

A hush falls over the room as a well modulated baritone voice begins, “Welcome to the Reading Room, my friends. We’re glad you could join our conversation. At the considerable risk of appearing sycophantic I am excruciatingly aware of punching above my weight class in this conversation.

Please join me in welcoming Brian Van Norman, author of the recently released novel Against the Machine: Luddites and, as you will learn, its sequel coming this fall with Guernica Editions: Against the Machine: Manifesto.

James: When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

Brian: Always a voracious reader from the age of three I was fascinated by the world presented to me through books. I first attempted writing when I was in a band at age 15 and wrote lyrics to our original songs. The concept of storytelling evolved from lyrics and I began to write short stories. I was a bit of a rebel and dropped the idea of writing for years in the pursuit of new experiences and eventually a university degree. Once I became an English and Theatre teacher I wrote some prize winning one act plays, short stories and poetry while I worked on research for what I hoped would be my first novel. So I suppose there was no one time when I consciously considered writing as a profession.

James: It sounds as if you were born to write.

Brian: Actually, thinking about it, it was always on my mind.

James: If you had a book club, what would it be reading and why?

Brian: I enjoy almost all genres of writing. I would suggest “War and Peace” by Tolstoy but in translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. This translation captures the simplicity of language Tolstoy employed as well as the power of his characters and plot. Simply put, one of the best novels ever written.

James: “War and Peace” 1,296 pages, I am impressed. I’m afraid that my attention span is too woefully transitory.

What do you like to do when you're not writing?

Brian: Before covid when I wasn’t writing I travelled. Both Susan, my wife, and I enjoy long stays in foreign parts. We’ve travelled to every Continent (including Antarctica) and sailed nearly every ocean or sea we could reach.

James: My wife, Christine, and I have enjoyed travel as well but our wanderings throughout most of North America in our motor home, a few islands in the Caribbean and Belize, Britain, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea and Hong Kong pale in comparison. Perhaps we could swap stories sometime?

Brian: That would be fun! I’d enjoy that too.

James: What tactics do you employ when writing? (For example: outline first or just write)

Brian: If I’m writing historical fiction I always look for ‘holes’ in history; those unexplained moments which allow me to fill that gap with both imagined and factual characters. For instance, Juan Ponce de Leon’s log from his second voyage to la Florida was lost. This allowed me to create that voyage in fiction with Immortal Water, my second novel. I tend to use a rough outline but the characters often lead me another way. That is the strangest thing about writing, how so often characters start to tell their own stories.

James: How very astute of you, Brian. You make it sound almost elementary but I know it is anything but.

Do you use any special writing software? If so what is it, and why do you like it?

Brian: I use Word for both writing and editing. I like it because it’s flexible.

James: I too use Word. I’m still using the 2007 version.

Tell us three things about yourself that might surprise your readers.

Brian: I have had three careers in my lifetime: as a teacher, a theatre director and adjudicator, and as a writer.

James: Why did you choose to write in your particular field or genre?

Brian: I have always had a strong interest in history and historical novels. It’s fascinating to know where we come from and how we arrived at the place we are now as a species. I enjoy the exploration of how ordinary people actually lived in their different societies, cultures and civilizations. Writers are often told “write what you know”. I love Canadian history, and since grade 7 when I was introduced to early French Canadian and Quebec history, I’ve always wanted to write about Wolfe and Montcalm. It turned out I found a ‘hole’ in history there. Too involved to explain here but it let to my first novel The Betrayal Path.

James: How would you describe Against the Machine: Luddites to someone who has not read any of your previous novels?

Brian: The novel is literary historical fiction based closely upon events and people in Yorkshire, England, in 1812. The story is told from the points of view of characters, both real and imagined, on both sides of the uprising by the Luddites.

James: What was the source of your inspiration for Against the Machine: Luddites?

Brian: I have a strong interest in the tools we humans have developed over the course of our history and the resulting consequences of invention, both positive and negative. As a result of discussions with Guernica Editions I have embarked on a somewhat unusual trilogy which features interactions between humans and machines in varied locations but 200 years apart. That said, Luddites was the initial novel set in Yorkshire in 1812. The sequel is Against the Machine: Manifesto, and is set in my home of Waterloo Region in 2012 (I am thankful I didn’t choose 2020) and will launch this autumn. The trilogy should culminate in a third book set in 2212… so I am writing in three different genres approaching this topic which I feel is so significant to our past, present and future.

James: What was your hardest chapter or scene to write?

Brian: In Luddites, the most difficult were the first four chapters which introduced quite a number of characters. I chose two separate social occasions on either side of the English class divide and used as much action as I could to garner interest in these individuals. The chapters contained many names which somewhat countered the purpose of most opening chapters: enticing the reader into the book.

James: Your characters are meticulously drawn, strong and well developed, although I must admit, the large number was somewhat challenging. However, from Mellor, the protagonist, down to the seemingly most insignificant character, I found myself empathizing with their profound moral dilemma in pursuit of freedom, justice and basic human rights.

Brian: I hope you found most of them interesting as you got to know each of them through the novel.

James: Which part of researching Against the Machine: Luddites was the most personally interesting to you? Were there any facts, symbols, or themes that you would have liked to include, but they just didn't make it into the story?

Brian: Most interesting to me were the moors of Yorkshire, their beauty and their menace, and a man who became a personal friend. I was lucky enough to meet Alan Brooke, whose ancestors were Luddites, who lives today in the cottage they built and is an expert on the subject. Without him to take me around to the old overgrown mills, or explain the complex geography, or guide me up into the moors, I really don’t think this book would have been finished.

As to what I would have liked to include, there are too many to name. The editing process, and the editors at Guernica Editions are masters at it, involves the removal of whatever is not furthering the novel’s impact. Every writer out there knows the pain of rejecting the words you’ve worked over, and then the delight when the edit process proves so effective.

James: Out of the protagonists: Juan Ponce de Leon or Ross Porter in Immortal Water; Alan Nashe in The Betrayal Path; or Ned Lud or George Mellor in Against the Machine: Luddites, that you’ve written about so far, which one do you feel you relate to the most?

Brian: Ross Porter. He is a mix of myself and a colleague, more so than any other of the characters I’ve written.

James: What are the ethics of writing about historical figures?

Brian: It’s important, I believe, to research historical characters as deeply as possible. It would be difficult to make Joseph Goebbels, for instance, an upstanding character. However, there’s a quote from Gabriel Garcia Márquez: “All human beings have three lives: public, private, and secret.” I think that most people do not believe they are evil or cause evil; they will rationalize their actions to make them agree with their moral code. A historian can cite the facts of a character and come to conclusions. A historical novelist is allowed more room to interpret, perhaps in bringing the secret life forward.

James: A most insightful and thought provoking premise, Brian. What advice would you give to a writer whose manuscript has been rejected several times and told he or she will never make it as a writer?

Brian: Keep writing. Keep submitting. I have a filing cabinet shelf full of rejections.

James: What is the most important tip you can share with other writers?

Brian: Be careful of vanity publishers or anyone who wants you to contribute financially. I made that mistake years back when I was desperate. They feed on fed up writers. Fortunately I got out of the contract due to a publishing flaw.

James: What was one challenge you had to overcome to become an author? How did you overcome that challenge?

Brian: I had to fight the negativity I received from so many rejections. I did stop writing for years at a time but always returned to it.

James: We’re very glad you possess such fortitude, Brian. What question do you wish that someone would ask about your books, but nobody has? Then answer it.

Brian: Question: Who is real and who isn’t in your novels?

Answer: None are real. They are all imaginary or interpreted.

The room is softly lit, the walls lined with deep rich mahogany shelves filled with books and as you enter you notice there are still a few empty seats. A low murmur of amiable voices gently greets your ears and immediately you sense you are among friends. You sink down into the arms of a luxuriously padded wing back chair savoring the feel and scent of its buttery soft leather as all your cares drift away.

A hush falls over the room as a well modulated baritone voice begins, “Welcome to the Reading Room, my friends. We’re glad you could join our conversation. At the considerable risk of appearing sycophantic I am excruciatingly aware of punching above my weight class in this conversation.

Please join me in welcoming Brian Van Norman, author of the recently released novel Against the Machine: Luddites and, as you will learn, its sequel coming this fall with Guernica Editions: Against the Machine: Manifesto.

James: When did you first realize you wanted to be a writer?

Brian: Always a voracious reader from the age of three I was fascinated by the world presented to me through books. I first attempted writing when I was in a band at age 15 and wrote lyrics to our original songs. The concept of storytelling evolved from lyrics and I began to write short stories. I was a bit of a rebel and dropped the idea of writing for years in the pursuit of new experiences and eventually a university degree. Once I became an English and Theatre teacher I wrote some prize winning one act plays, short stories and poetry while I worked on research for what I hoped would be my first novel. So I suppose there was no one time when I consciously considered writing as a profession.

James: It sounds as if you were born to write.

Brian: Actually, thinking about it, it was always on my mind.

James: If you had a book club, what would it be reading and why?

Brian: I enjoy almost all genres of writing. I would suggest “War and Peace” by Tolstoy but in translation by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky. This translation captures the simplicity of language Tolstoy employed as well as the power of his characters and plot. Simply put, one of the best novels ever written.

James: “War and Peace” 1,296 pages, I am impressed. I’m afraid that my attention span is too woefully transitory.

What do you like to do when you're not writing?

Brian: Before covid when I wasn’t writing I travelled. Both Susan, my wife, and I enjoy long stays in foreign parts. We’ve travelled to every Continent (including Antarctica) and sailed nearly every ocean or sea we could reach.

James: My wife, Christine, and I have enjoyed travel as well but our wanderings throughout most of North America in our motor home, a few islands in the Caribbean and Belize, Britain, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea and Hong Kong pale in comparison. Perhaps we could swap stories sometime?

Brian: That would be fun! I’d enjoy that too.

James: What tactics do you employ when writing? (For example: outline first or just write)

Brian: If I’m writing historical fiction I always look for ‘holes’ in history; those unexplained moments which allow me to fill that gap with both imagined and factual characters. For instance, Juan Ponce de Leon’s log from his second voyage to la Florida was lost. This allowed me to create that voyage in fiction with Immortal Water, my second novel. I tend to use a rough outline but the characters often lead me another way. That is the strangest thing about writing, how so often characters start to tell their own stories.

James: How very astute of you, Brian. You make it sound almost elementary but I know it is anything but.

Do you use any special writing software? If so what is it, and why do you like it?

Brian: I use Word for both writing and editing. I like it because it’s flexible.

James: I too use Word. I’m still using the 2007 version.

Tell us three things about yourself that might surprise your readers.

Brian: I have had three careers in my lifetime: as a teacher, a theatre director and adjudicator, and as a writer.

James: Why did you choose to write in your particular field or genre?

Brian: I have always had a strong interest in history and historical novels. It’s fascinating to know where we come from and how we arrived at the place we are now as a species. I enjoy the exploration of how ordinary people actually lived in their different societies, cultures and civilizations. Writers are often told “write what you know”. I love Canadian history, and since grade 7 when I was introduced to early French Canadian and Quebec history, I’ve always wanted to write about Wolfe and Montcalm. It turned out I found a ‘hole’ in history there. Too involved to explain here but it let to my first novel The Betrayal Path.

James: How would you describe Against the Machine: Luddites to someone who has not read any of your previous novels?

Brian: The novel is literary historical fiction based closely upon events and people in Yorkshire, England, in 1812. The story is told from the points of view of characters, both real and imagined, on both sides of the uprising by the Luddites.

James: What was the source of your inspiration for Against the Machine: Luddites?

Brian: I have a strong interest in the tools we humans have developed over the course of our history and the resulting consequences of invention, both positive and negative. As a result of discussions with Guernica Editions I have embarked on a somewhat unusual trilogy which features interactions between humans and machines in varied locations but 200 years apart. That said, Luddites was the initial novel set in Yorkshire in 1812. The sequel is Against the Machine: Manifesto, and is set in my home of Waterloo Region in 2012 (I am thankful I didn’t choose 2020) and will launch this autumn. The trilogy should culminate in a third book set in 2212… so I am writing in three different genres approaching this topic which I feel is so significant to our past, present and future.

James: What was your hardest chapter or scene to write?

Brian: In Luddites, the most difficult were the first four chapters which introduced quite a number of characters. I chose two separate social occasions on either side of the English class divide and used as much action as I could to garner interest in these individuals. The chapters contained many names which somewhat countered the purpose of most opening chapters: enticing the reader into the book.

James: Your characters are meticulously drawn, strong and well developed, although I must admit, the large number was somewhat challenging. However, from Mellor, the protagonist, down to the seemingly most insignificant character, I found myself empathizing with their profound moral dilemma in pursuit of freedom, justice and basic human rights.

Brian: I hope you found most of them interesting as you got to know each of them through the novel.

James: Which part of researching Against the Machine: Luddites was the most personally interesting to you? Were there any facts, symbols, or themes that you would have liked to include, but they just didn't make it into the story?

Brian: Most interesting to me were the moors of Yorkshire, their beauty and their menace, and a man who became a personal friend. I was lucky enough to meet Alan Brooke, whose ancestors were Luddites, who lives today in the cottage they built and is an expert on the subject. Without him to take me around to the old overgrown mills, or explain the complex geography, or guide me up into the moors, I really don’t think this book would have been finished.

As to what I would have liked to include, there are too many to name. The editing process, and the editors at Guernica Editions are masters at it, involves the removal of whatever is not furthering the novel’s impact. Every writer out there knows the pain of rejecting the words you’ve worked over, and then the delight when the edit process proves so effective.

James: Out of the protagonists: Juan Ponce de Leon or Ross Porter in Immortal Water; Alan Nashe in The Betrayal Path; or Ned Lud or George Mellor in Against the Machine: Luddites, that you’ve written about so far, which one do you feel you relate to the most?

Brian: Ross Porter. He is a mix of myself and a colleague, more so than any other of the characters I’ve written.

James: What are the ethics of writing about historical figures?

Brian: It’s important, I believe, to research historical characters as deeply as possible. It would be difficult to make Joseph Goebbels, for instance, an upstanding character. However, there’s a quote from Gabriel Garcia Márquez: “All human beings have three lives: public, private, and secret.” I think that most people do not believe they are evil or cause evil; they will rationalize their actions to make them agree with their moral code. A historian can cite the facts of a character and come to conclusions. A historical novelist is allowed more room to interpret, perhaps in bringing the secret life forward.

James: A most insightful and thought provoking premise, Brian. What advice would you give to a writer whose manuscript has been rejected several times and told he or she will never make it as a writer?

Brian: Keep writing. Keep submitting. I have a filing cabinet shelf full of rejections.

James: What is the most important tip you can share with other writers?

Brian: Be careful of vanity publishers or anyone who wants you to contribute financially. I made that mistake years back when I was desperate. They feed on fed up writers. Fortunately I got out of the contract due to a publishing flaw.

James: What was one challenge you had to overcome to become an author? How did you overcome that challenge?

Brian: I had to fight the negativity I received from so many rejections. I did stop writing for years at a time but always returned to it.

James: We’re very glad you possess such fortitude, Brian. What question do you wish that someone would ask about your books, but nobody has? Then answer it.

Brian: Question: Who is real and who isn’t in your novels?

Answer: None are real. They are all imaginary or interpreted.

Q-and-A: Middle instalment of Waterloo Region author's tech trilogy hits shelves

Waterloo Chronicle

The first of October is bringing the second book of a tech trilogy from local author Brian Van Norman.

The novel, “Against the Machine: Manifesto” is set in 2012 in Waterloo Region. It’s about a successful family man who loses his job in a corporate downsize and turns terrorist to convey his plight to an uncaring public. The novel, though it stands alone, is a sequel to the critically acclaimed “Against the Machine: Luddites,” says Van Norman's website.

Heading into the release date, Van Norman participated in a Q-and-A.

Q: THE NEW BOOK IS OUT OCT. 1. CAN YOU SUM UP ITS CONTENT ... AND MAYBE SHARE SOMETHING QUIRKY THAT TOOK PLACE WHILE WRITING IT?

A: Mel Buckworth, dependable family man, loses his manufacturing job through recession. Having lost his sense of purpose, his pride sidelines him and creates an increasing bitterness as he discerns his lack of digital skills so apparent in his children’s generation.

As Mel desperately attempts to find equilibrium, he estranges his family, leaves his wife and enlists the help of a greedy grad student. Will Baker teaches Mel the skills he will need to wreak revenge on a system seemingly discarding him. Slowly, he becomes an obsessed terrorist delivering his message that humans will succumb to machines and the social system controlling them.

As his acts grow more lethal, Mel knows he must make an indelible declaration. A “manifesto” to be remembered.

Q: YOU HAVE APPARENTLY GONE TO EVERY CONTINENT AND "SAILED NEARLY EVERY SEA ON THE PLANET." CAN YOU RELAY A STORY?

A: Antarctica, visiting a scientific station surrounded by 50,000 penguins. Penguins eat krill. Krill is pink. So is the ice where the penguins live and defecate. You can smell it from at least five kilometres’ distance.

Q: IT'S A RANDOM SATURDAY NIGHT, AND YOU HAVE NO FORMAL OBLIGATIONS. WHAT MIGHT YOU BE UP TO?

A: Most often, it’s dinner with friends. My wife, Susan, is a fine chef, with recipe books from around the world. I keep my distant friends close with WhatsApp, FaceTime and Skype.

Q: STRANDED. DESERT ISLAND, AS THEY SAY. WHICH THREE BOOKS WOULD YOU BRING WITH YOU? AND WHICH THREE ALBUMS?

A: Besides mine? Ha! “War and Peace.” “Lord of the Rings.” “The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.” Oh, and a necessary fourth: “Robinson Crusoe.”

Three albums … Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” by Glenn Gould. “Thaïs” by Massenet. “Sgt. Pepper’s” by the Beatles.

Q: HOW ARE YOU TAKING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC?

A: COVID has made me a bit of an introvert. Currently, I don’t often go out. Thus, I can’t make book appearances other than through Zoom with my new novel.

Q: AUTHORING IN 2021: WHAT'S A PARTICULAR CHALLENGE?

A: Guernica Editions, my publisher, whose logo says “No Borders, No Limits,” proves it constantly with their publications. In my case, they have given me the opportunity to write a trilogy on the theme of Human/Machine interface.

I have completed a historical novel called “Against the Machine: Luddites” termed by one critic: “Jane Austen meets Quentin Tarantino,” set in 1812 Yorkshire, England, during the terrible rebellion there.

The second book is set in 2012, a contemporary-style novel with another critic saying, “Breaking Bad Comes to Waterloo.” It is called “Against the Machine: Manifesto,” set in Waterloo Region!

The third of the trilogy, tentatively called “Against the Machine: Evolution,” is a novel in progress and is set in Toronto MEG, 2212 and is, obviously, speculative fiction.

So I have the chance to write three standalone novels in three different styles, independent of each other, yet forming the thematic connection of the Human/Machine interface.

That … is a challenge, believe me!

Waterloo Chronicle

The first of October is bringing the second book of a tech trilogy from local author Brian Van Norman.

The novel, “Against the Machine: Manifesto” is set in 2012 in Waterloo Region. It’s about a successful family man who loses his job in a corporate downsize and turns terrorist to convey his plight to an uncaring public. The novel, though it stands alone, is a sequel to the critically acclaimed “Against the Machine: Luddites,” says Van Norman's website.

Heading into the release date, Van Norman participated in a Q-and-A.

Q: THE NEW BOOK IS OUT OCT. 1. CAN YOU SUM UP ITS CONTENT ... AND MAYBE SHARE SOMETHING QUIRKY THAT TOOK PLACE WHILE WRITING IT?

A: Mel Buckworth, dependable family man, loses his manufacturing job through recession. Having lost his sense of purpose, his pride sidelines him and creates an increasing bitterness as he discerns his lack of digital skills so apparent in his children’s generation.

As Mel desperately attempts to find equilibrium, he estranges his family, leaves his wife and enlists the help of a greedy grad student. Will Baker teaches Mel the skills he will need to wreak revenge on a system seemingly discarding him. Slowly, he becomes an obsessed terrorist delivering his message that humans will succumb to machines and the social system controlling them.

As his acts grow more lethal, Mel knows he must make an indelible declaration. A “manifesto” to be remembered.

Q: YOU HAVE APPARENTLY GONE TO EVERY CONTINENT AND "SAILED NEARLY EVERY SEA ON THE PLANET." CAN YOU RELAY A STORY?

A: Antarctica, visiting a scientific station surrounded by 50,000 penguins. Penguins eat krill. Krill is pink. So is the ice where the penguins live and defecate. You can smell it from at least five kilometres’ distance.

Q: IT'S A RANDOM SATURDAY NIGHT, AND YOU HAVE NO FORMAL OBLIGATIONS. WHAT MIGHT YOU BE UP TO?

A: Most often, it’s dinner with friends. My wife, Susan, is a fine chef, with recipe books from around the world. I keep my distant friends close with WhatsApp, FaceTime and Skype.

Q: STRANDED. DESERT ISLAND, AS THEY SAY. WHICH THREE BOOKS WOULD YOU BRING WITH YOU? AND WHICH THREE ALBUMS?

A: Besides mine? Ha! “War and Peace.” “Lord of the Rings.” “The Complete Works of William Shakespeare.” Oh, and a necessary fourth: “Robinson Crusoe.”

Three albums … Bach’s “Goldberg Variations” by Glenn Gould. “Thaïs” by Massenet. “Sgt. Pepper’s” by the Beatles.

Q: HOW ARE YOU TAKING THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC?

A: COVID has made me a bit of an introvert. Currently, I don’t often go out. Thus, I can’t make book appearances other than through Zoom with my new novel.

Q: AUTHORING IN 2021: WHAT'S A PARTICULAR CHALLENGE?

A: Guernica Editions, my publisher, whose logo says “No Borders, No Limits,” proves it constantly with their publications. In my case, they have given me the opportunity to write a trilogy on the theme of Human/Machine interface.

I have completed a historical novel called “Against the Machine: Luddites” termed by one critic: “Jane Austen meets Quentin Tarantino,” set in 1812 Yorkshire, England, during the terrible rebellion there.

The second book is set in 2012, a contemporary-style novel with another critic saying, “Breaking Bad Comes to Waterloo.” It is called “Against the Machine: Manifesto,” set in Waterloo Region!

The third of the trilogy, tentatively called “Against the Machine: Evolution,” is a novel in progress and is set in Toronto MEG, 2212 and is, obviously, speculative fiction.

So I have the chance to write three standalone novels in three different styles, independent of each other, yet forming the thematic connection of the Human/Machine interface.

That … is a challenge, believe me!

Susan, without whom none of this would have happened.

Proudly powered by Weebly